Nick Beckett, Managing Partner of Beijing Office and Co-Head of Life Sciences & Healthcare Group, CMS

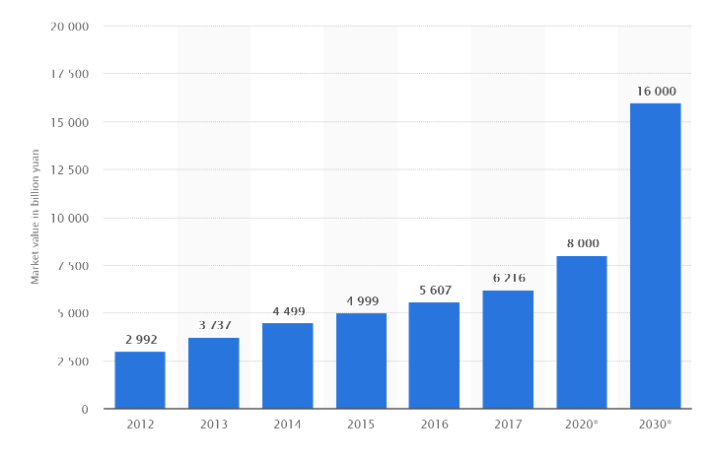

China’s rapid GDP growth to become the world’s second largest economy is reflected across almost all of its industry sectors, including healthcare. Between 2010 and 2017, China’s healthcare market increased in size by over 200% and the government aims to see this growth continue. Figures published in Healthy China 2030, one of the Chinese government’s flagship healthcare policies, reveal the aim to grow healthcare spending to 8000bn RMB by 2020 and increase this to 16,000bn RMB by 2030.

There are a number of factors which demand and stimulate growth in China’s healthcare sector, China’s move from being a manufacturing-based to a more consumer-based economy being one. An even more significant factor is China’s aging population. By 2050, it is estimated 80% of the world’s elderly will be Chinese.

Graph: Growth of China’s Healthcare market between 2012 and 2017 and its predicted growth in 2020 and 2030. Source: Open source reports.

Traditionally a lack of robust IP protection was considered as a significant problem for multinationals, as well domestic companies, wanting to enter the healthcare market in China. What’s more it also stunted innovation. However, due to this changing environment, the Chinese government is enacting numerous policies, laws and regulations to continue to encourage the development of their domestic healthcare market.

One such piece of legislation which has attracted significant attention recently is the new Foreign Investment Law (the ‘FIL’). Article 22 of the FIL explicitly protects the IP rights of foreign-related companies in China and prevents forced technology transfers. This is one of the key talking points in the current US-China trade war. Although some in China say the new FIL does not go far enough and some in particular say Article 22 is ineffective in its current form, it will go some way to provide a sense of security to foreign companies who hope to enter the Chinese market.

China has also recently updated their patent regime with the release of a draft amendment to the PRC Patent Law at the turn of the year. As part of China’s healthcare reform, an amendment has been included in this draft law, which provides a 5-year patent extension for innovative drugs. In healthcare in particular, the prospects of the Chinese market is extremely alluring. The introduction of the new FIL and the PRC Patent Law amendment demonstrates the government’s intention of creating a more robust system capable of attracting domestic and international investment.

Around the same time the new FIL was approved, one of China’s key policies involving healthcare appeared to have been dropped. Made in China 2025 (‘MIC 25’) is one of the government’s headline policies which looks to see China become globally dominant in high-tech manufacturing, including high-end equipment and biomedicine. The policy is another key feature in the trade-war. The US argues that China is using unfair subsidies to boost their domestic industry to achieve their MIC 25 goals and this is manipulating the free-market. Li Keqiang, the Premier of China, made no mention of MIC 25 directly in his speech at this year’s plenary session presumably as a concession to the US. However, the substance of his speech made it clear that China will continue to drive their high-tech industries forward and their goals are very much unchanged.

One policy that remains at the forefront of the healthcare sector in China is Healthy China 2030 (HC 30). HC30 makes public health the key consideration in future social and economic developments. On 29 May 2019, the Healthy China Nutrition Union was launched in Beijing. The new union is focussed on bringing partners together across the healthcare sector to improve national health.

Finally, a key area the government is trying to grow in order to reach their goals set out in HC 30 is e-health. With over 750 million smart phone users in China the potential for the e-health market is significant.

Three new pieces of legislation have been introduced in the last year which aim to provide a regulatory framework in this new technology-dependent market. The Measures for the Administration of Internet-based Diagnosis and Treatment, the Measures for the Administration of Internet Hospitals and the Measures for the Administration of Telemedicine were enacted concurrently by the National Health Commission. Their enactment is an acknowledgement by Beijing of the importance of the emerging e-health sector in China.

China’s internet giants have recognised the new opportunities in the e-health market. Tencent’s Doctorwork has recently merged with Trusted Doctors to create Tencent Trusted Doctors. This company is now the biggest healthcare services platform in China, connecting 440,000 doctors, 10 million patients and more than 30,000 hospitals. According to Sootoo Research Institute, China’s internet healthcare market could be worth as much as RMB 90bn by 2020.

The investment in e-health is not only from domestic companies. There are now numerous Chinese companies in this field collaborating with companies from across the world. XtalPi, is an AI company that stimulates solid compounds to accelerate the clinical testing rounds of R&D. This company has received support from Tencent, Google and Pfizer and is now expanding globally. This is a good example of the MIC 25 goals already being achieved.

The rate of change in China’s healthcare market is unlikely to slow any time soon. The government have made their intentions clear that they are going to expand this sector and provide greater access and higher quality healthcare to the population. The legal framework is providing a base for new industries to emerge and companies to grow in China. Further, developments like the new FIL and Patent Law are encouraging even more foreign investment. China has now become a hotbed for healthcare innovation and it is very likely that a number of significant healthcare developments in the future will come from China.